The reality of foie gras in Switzerland

- Stop Gavage Suisse

- 12 janv. 2019

- 14 min de lecture

Dernière mise à jour : 3 nov. 2023

Analysis of the November 2018 DemoScope survey

How does Switzerland position itself with regard to foie gras?

We intuitively knew that there were big differences between the French- and German-speaking regions of Switzerland in terms of foie gras consumption, but we didn't know to what extent.

In addition, we wanted to learn more about the differences between men and women, as well as according to age and socio-professional categories.

In order to get a clearer idea, Stop Gavage Switzerland, in partnership with the association Four Paws Switzerland, carried out a nationwide survey in December 2018 (survey conducted by the Demoscope institute).

Illustrations of some of the results of the survey conducted with Four Paws Switzerland

Survey questions

Question 1: How often do you eat foie gras?

Question 2: What are the reasons for consuming foie gras?

Question 3: What is the alternative consumption in the event of a ban ?

Question 4: What are the reasons for not consuming foie gras ?

Question 5: Would you try vegan foie gras ?

Question 6: Do you consider force-feeding to be animal abuse?

Question 7: To what extent do you consider the foie gras trade to be a form of animal abuse contrary to public morality?

Question 8: Did you know that the practice of force-feeding is prohibited in Switzerland?

Question 9 : Did you know that magret comes from the production of foie gras?

Each of the questions was detailed according to different factors:

the linguistic region: German-speaking Switzerland, French-speaking Switzerland or Ticino

gender: male or female

age range: 15-34, 35-54 and 55-74 years old

level of education: compulsory/secondary or higher education

income level: less than 5,000, between 5,000 and 9,000 or more than 9,000 Swiss francs per month

the place of residence: urban or rural area

N/P in the answers means Don't know / No answer.

Given the size of the sample (just over 1,000 people), the margin of error on the overall results is approximately 3%. This margin of error increases when questions are asked of a smaller sample, especially the single consumer sample (about 300 people), where it rises to 5.6%.

The results are as follows

In this chapter, we will present and comment on the results obtained for the different questions. We first present the results for Switzerland as a whole, although questions 2, 3 and 4 are not addressed to all respondents. Questions 2 and 3 are addressed only to consumers of foie gras while question 4 is addressed only to non-consumers. Then, for each question, we will look at the most striking results according to the different factors.

Question 1: How often do you consume foie gras?

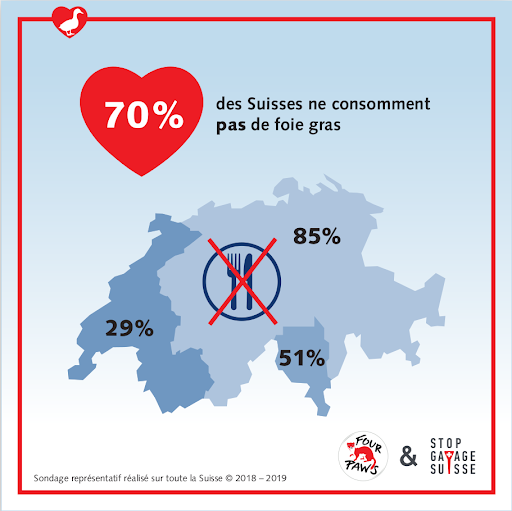

70% of the Swiss population does not consume foie gras.

The result is encouraging and reassures us in our action. On the one hand, a total ban on the product would be of no consequence for the majority of people. On the other hand, if we came to a popular initiative, we would win a priori, provided that the non-consumers pronounce themselves in coherence with their practice.

What factors influence this result?

The first and main factor linked to whether or not a person consumes foie gras is his or her linguistic region, and therefore his or her place of living.

70% of the French-speaking Swiss consume it, while only 13% of the Swiss German do. The Ticino is somewhere in between, with 49% of its population consuming foie gras.

Other characteristics have little influence on this result.

An income level of over 9,000 Swiss francs slightly favours consumption compared to lower incomes (36% versus 23%).

Those with a higher level of education are slightly more inclined to consume foie gras (33%) than those with compulsory or secondary education (24%).

It can be seen that gender does play a small role in the consumption of foie gras. Men are 33% while women are only 24%.

While age does not play a significant role, there is a slight predominance of those over 35 years of age (31% as opposed to 25%).

And finally, the place of residence, whether urban or rural, does not count at all (1% difference, not representative).

To caricature, the typical consumer is a man from French-speaking Switzerland, aged over 35, with an income of over 9,000 Swiss francs and a higher level of education.

In contrast, the typical non-consumer is a Swiss-German woman under 35 years of age, with an income level of less than 9,000 Swiss francs and no higher education.

Question 2: What are the reasons for consuming foie gras?

This question is addressed only to consumers, i.e. 29% of the population.

Among foie gras consumers, it is the taste of the product that is mentioned as the reason for their consumption in the first place, far ahead of other reasons. This result is both encouraging and troublesome.

It is encouraging because taste is something that evolves and is educable.

On the other hand, it is troublesome because, by definition, taste is not debatable. Because of this, today's consumers allow themselves to get rid of ethical considerations when discussing foie gras.

The second reason is the availability of the product, the opportunity to eat it, because they are offered it. This is a rather weak reason: if the product were to become unavailable, in shops and restaurants and on festive tables, more than 20% of today's consumers would stop eating it and would not mind it.

Tradition comes in third place, for only 11% of consumers, although it is often the first argument put forward to maintain the current status quo.

What factors influence this result?

As far as the reasons for consumption are concerned, it is rather the level of education and income that will distinguish foie gras consumers.

The level of education has a slight influence on the taste argument, with 66% for compulsory and secondary school, compared with 80% for higher education.

A lower income (less than 5,000 Swiss francs) reduces the taste argument (60% versus 77%), and increases the opportunity argument (33% versus 25%).

Surprisingly, the middle class is slightly different with the “tradition” argument (16% versus

6%).

The linguistic region plays little part in the reasons put forward:

For taste, there is no difference between German-speaking Switzerland and Ticino, with around 70% of consumers mentioning this reason, and around 80% in French-speaking Switzerland.

For opportunity, Ticino is the region that mentions this reason the most, with more than 33%, compared with around 25% in the German and French-speaking parts of Switzerland.

For tradition, Romandy emphasises it at 16% compared to less than 10% for the other two linguistic regions. We can see that even in Romandie this reason is not so important.

The under 35s differ slightly from their elders by invoking opportunity more often (67% versus 80%) than taste (32% versus 22%).

The countryside differs from the city with a preference for the argument of opportunity (30% versus 23%) over the argument of taste (68% versus 77%).

The male-female difference is not at all significant, whatever the reason given.

Question 3: What is the alternative consumption in the event of a ban?

This question too is only addressed to consumers, i.e. 29% of the population.

In the event of a ban, 38% of consumers say they would be prepared to go to France or elsewhere to get it, and therefore ignore the ban. This shows us that in the event of a ban, if it also affects private individuals, surveillance measures will have to be put in place, at least initially.

Other consumers would turn to normal liver pâté and Swiss products. Swiss farmers would thus have every reason to want a ban on foie gras. It is estimated that Swiss consumers spend more than 60 million Swiss francs on foie gras every year; the Swiss agricultural sector could hope to recoup at least a third of this sum. Foie gras obtained without force-feeding would not replace force-fed foie gras.

What factors influence this result?

The first three criteria that distinguish consumers of foie gras in the event of a ban are gender, level of education and language region.

More men (44%) than women (28%) plan to go abroad to bring foie gras back to Switzerland. They are less willing to opt for normal liver pâté (25% versus 34%) or non-force fed foie gras (7% versus 14%).

People with a higher education are more inclined to go abroad for foie gras (44% versus 26%) and to try on-force fed foie gras (13% versus 5%); on the other hand, they are less inclined to turn to Swiss products (30% versus 43%).

Unsurprisingly, it is in the French-speaking part of Switzerland that there is the highest proportion of people willing to go abroad to get foie gras (44%), whereas there are only 30% in the German-speaking part of Switzerland and 25% in Ticino. It should be noted in the event of a ban, many people would likely go buy this product in France. The Swiss customs figures are lower (by 20%) than what the French Ministry announces for foie gras sales in Switzerland.

The French-speaking Swiss would then fall back on Swiss products and normal liver pâté by 31%, while people in the Ticino region would do so by 44%. These two regions are not interested in non-force fed foie gras (7%). The German-speaking part of Switzerland is more likely to taste non-force fed foie gras (14%), to the detriment of normal foie gras (24%).

Age is of little relevance when it comes to going abroad to get foie gras.

It can be seen that the over 55s are less inclined to go for Swiss products (28% versus 38%) or non-force fed foie gras (3% versus 13%).

Those on lower incomes (less than 5,000 Swiss francs) are less willing to go abroad to buy foie gras (24% as opposed to 38%) and less willing to try non-force fed foie gras (4% as opposed to 11%).

In the countryside, people are less willing to replace foie gras with normal liver pâté (23% versus 31%), but more willing to try non-force fed foie gras (14% versus 9%).

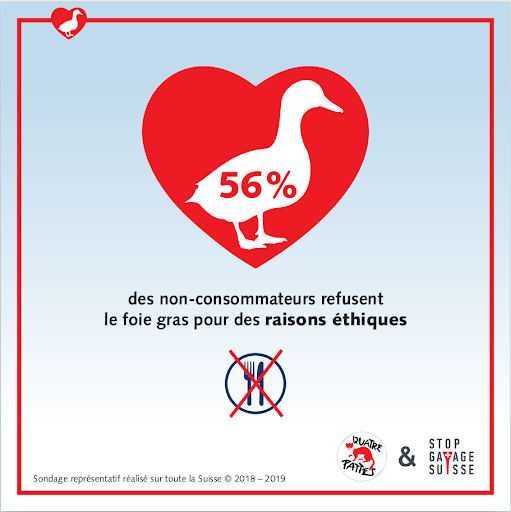

Question 4: What are the reasons for not eating foie gras?

This question is only for non-consumers, i.e. 70% of the population.

Note: the sum of the answers does not add up to 100%, as each respondent was able to give several answers.

We can see that the first reason, by far, is ethical.

Taste also plays an important role in the choice to consume or not to consume foie gras. The argument in defence of foie gras, which is based on the fact that it is exceptional from a taste point of view, does not hold up, because a large number of people do not like the taste of it. In this survey, in absolute terms, 219 people do not like the taste of foie gras, compared to 258 who eat it because they like the taste of it. This result shows that the taste argument is not admissible and confirms that it should be definitively excluded from discussions about foie gras.

We also note that 12% of people do not eat it because they consider it is not traditional. This is the opposite of the 13% of consumers who eat it traditionally. Nor can tradition be an argument put forward in the debates around foie gras: not only do few people consider it as such, but it acts in both directions in equal value.

What factors influence this result?

What distinguishes the reasons for non-consumption are age and linguistic region in the first place.

Ethics is the main reason for the over-55s, with 70%, while taste only weighs in at 18%. Among the youngest, the ethical reason is only 44%, while taste is only 31%.

The reasons for not consuming alcohol also depend strongly on the linguistic region. 58% of Swiss Germans reject it out of ethical reasons, compared with 43% of Swiss French-speakers and only 34% of Swiss Ticino.

Taste is the reason for 41% of the Ticino and 37% of the French-speaking Swiss, compared with only 26% of the Swiss German.

Tradition is mentioned more often by the Ticino (24%) and the Swiss German (13%) than by the French-speaking Swiss (6%).

Living in the countryside or in the city has a slight influence on the ethical argument, which is higher in the city (58% versus 49%).

The level of education also gives a slight advantage to the ethical argument among the beneficiaries of higher education (60% versus 50%).

Gender also has a slight influence on the ethical argument, with a preference among women (60% versus 52%).

Question 5: Would you try vegan foie gras?

On the whole, only a third of the population say they would try vegan foie gras.

Vegan foie gras means vegan alternatives to foie gras.

The promotion of vegan alternatives therefore does not seem to be the right way to get the population to turn away from foie gras. This result is not surprising because it is clear that if people consume foie gras it is because they consider it to be a specific product that they do not think they can replace.

We can also see that few people have tried vegan foie gras (less than 5%).

What factors influence this result?

The main factor influencing the results is age.

47% of people under 35 want to try it, compared to 24% of those over 35.

Younger people are also less opposed than others to the idea of trying it, with 43% versus 65% respectively.

Curiosity also stands out slightly among consumers of foie gras (34% versus 26%), city dwellers (34% versus 26%) and those with higher education (36% versus 27%).

The linguistic region confirms the results of the consumers: fewer Swiss Germans want to try vegan foie gras (29%) than those from the French-speaking part of Switzerland and Ticino (39%).

It is understandable that most non-consumers are less inclined to try an alternative to foie gras. After all, they don't miss it or are even disgusted by it. They have less reason to seek an alternative to replace it.

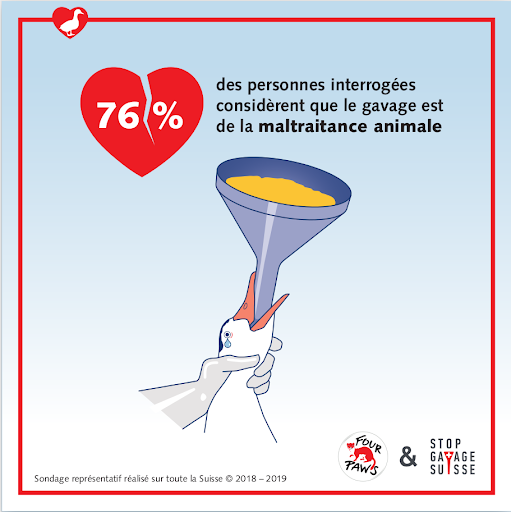

Question 6: Do you equate force-feeding with animal abuse?

This result is indisputable: three quarters of the population knows and recognises that force-feeding is animal abuse, whatever the industry may say.

What factors influence this result?

There is a very big difference between consumers and non-consumers: only 55% of the consumers consider force-feeding to be animal abuse, compared to 85% of non-consumers. This result can be understood in terms of the effort that consumers must make to reduce the cognitive dissonance linked to the fact that they participate indirectly in the practice of force-feeding. What seems alarming, however, is that more than half of them consume it while being aware of the suffering caused.

This result differs from one linguistic region to another: 82% of Swiss German-speaking people think that force-feeding is animal abuse, compared to 72% in Ticino and only 60% in French-speaking Switzerland, where it is much more common.

Question 7: To what extent do you consider the foie gras trade to be contrary to public morality?

This question was asked with reference to Article XX-a of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). This article describes the exceptions to the obligation of free trade:

Article XX: General exceptions

Provided that such measures are not applied in such a manner as to constitute a means of arbitrary or unjustifiable discrimination between countries where the same conditions prevail, or a disguised restriction on international trade, nothing in this Agreement shall be construed to prevent the adoption or application by any contracting party of such measures.

a necessary for the protection of public morals ;

b necessary for the protection of the health and life of humans; b necessary for the protection of the health and life of humans

and animals or plant preservation;

[...]

Two thirds of the population would thus be of the opinion that the foie gras trade is contrary to public morality. This result reinforces our view that if Switzerland is attacked before the World Trade Organization (WTO) for failing to comply with free trade agreements, it will win the case, as happened with the EU against Canada over the ban on seal products in 2013.

What factors influence this outcome?

As the question is similar to question 6, we find the same results: consumers are less likely to see a public morality issue (39%) than non-consumers (77%). This result differs from one linguistic region to another.

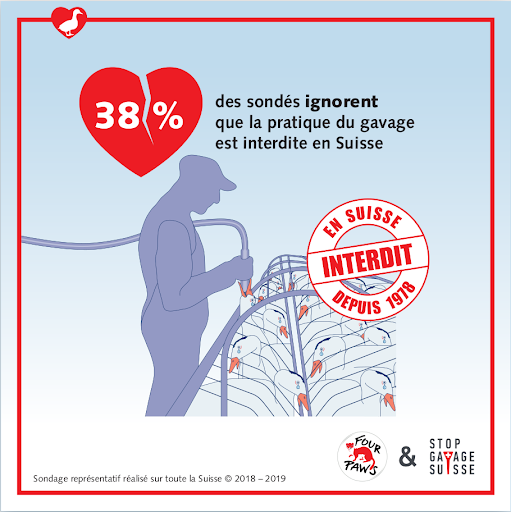

Question 8: Did you know that the practice of force-feeding is prohibited in Switzerland?

It can be seen here that a large part of the population is not aware that force-feeding is prohibited in Switzerland, even though this ban has existed for more than 40 years.

We can see that there is still a lot of work to do to inform the population about foie gras in Switzerland. And we can assume that if more people knew about this ban, there would also be more people in favour of banning the foie gras trade.

What factors influence this result?

Very clearly, it is age that makes the difference. Sixty-nine percent of those over 55 are aware that force-feeding is prohibited in Switzerland. 61% of those aged 35-55 are aware of this, while only 44% of those under 35 are aware of it.

It is clear that the presence of foie gras on supermarket shelves suggests that there is no problem with this product (If it were forbidden, we wouldn't see it in the shops!). Moreover, the ban took place more than 40 years ago. Older people may remember the debates on the issue.

It is also noticeable that the level of income slightly marks the outcome. Those earning less than 5,000 Swiss francs per month are less informed (49% versus 60%).

However, it is noticeable that consumers and non-consumers are equally well informed about the ban (53% versus 59%). Cognitive dissonance has little to do with this.

More information on the ban on force-feeding might reveal a variation between the two categories.

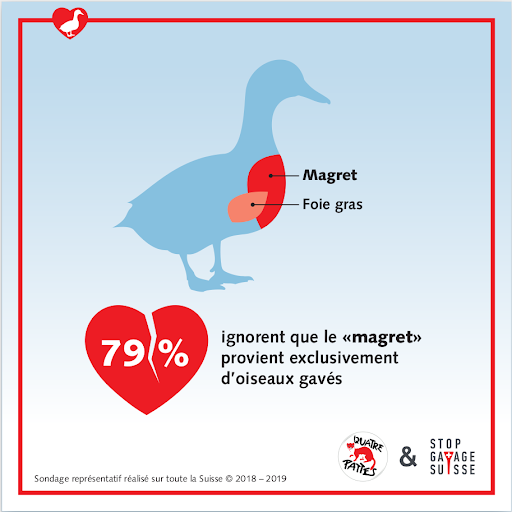

Question 9: Did you know that magret (duck breast) comes from the production of foie gras?

Here again, there is a flagrant lack of information among the Swiss population.

Let's bet that with better information, consumption of magret will decrease.

In general, we can assume that better information on the production methods of animal products will lead to a decrease in consumption. This is why the ethical problems posed by animal husbandry and slaughter are constantly hidden by the industries involved in these two activities.

What factors influence this outcome?

Although somewhat less marked than on the question of the ban on force-feeding in Switzerland, the difference here too is between consumers and non-consumers (23% versus 13%). Foie gras eaters are more likely to know how the magret (duck breast) is made. This is not surprising, because on the markets, in any case, the foie gras stands often also sell magret.

As before, this result differs from one linguistic region to another: in French-speaking Switzerland 29% of people are informed, compared to 14% in Ticino and 12% in German-speaking Switzerland.

Conclusion

We can now improve both our consumer and non-consumer foie gras profiles with detailed results.

The typical consumer

As we have seen, the typical consumer is a man, from French-speaking Switzerland, over 35 years old, with an income level of over 9,000 Swiss francs and with a higher level of education.

With regard to the previous analyse, we can add that:

he eats foie gras by taste, and that tradition does not influence his choice to consume it;

in the event of a ban, he would go to France to get some, but he would be interested in tasting non-force fed foie gras;

he is not really interested in tasting vegan foie gras;

he doesn't really think that the practice of force-feeding is animal abuse;

he doesn't agree with the idea that trading foie gras is contrary to public morality;

he knows that the practice of force-feeding is forbidden in Switzerland;

he knows that magret (duck breast) comes from the production of foie gras.

The typical non-consumer

As mentioned above, the typical non-consumer is a Swiss-German woman under 35 years of age, with an income level of less than 5,000 Swiss francs and no higher education.

With regard to the previous analyses, we can add that:

she does not eat foie gras for ethical reasons above all and that she does not necessarily like the taste either. The fact that it is not traditional doesn't influence her choice;

she would gladly try vegan foie gras;

she takes it for granted that the practice of force-feeding is animal abuse;

she agrees with the idea that trading in foie gras is contrary to public morality;

she is not necessarily aware that the practice of force-feeding is forbidden in Switzerland;

she does not know that the magret (duck breast) comes from the production of foie gras.

What can we learn from this survey?

We knew that the linguistic region was decisive. As we expected, because of their proximity to French gastronomic culture, the French-speaking Swiss are the main consumers of foie gras. What was unknown prior to the survey was the proportion of consumers in the French-speaking part of Switzerland, as well as in Ticino, which we had no idea about. Today we can see that the proportion of Ticino consumers is somewhere between the French-speaking Swiss and the Swiss Germans.

We realise that taste plays a dominant role in both eating and not eating foie gras; contrary to tradition.

Non-consumers are very sensitive to the ethical argument.

Consumers would gladly go and get foie gras from abroad. But it would be Swiss products that would be the first to benefit from a ban on foie gras. We should be able to appeal for solidarity with Swiss farmers in support of a ban.

Generally speaking, vegan foie gras is of no interest to either consumers or non-consumers. It is questionable whether it is worth putting a lot of energy into this kind of alternative.

It would seem that it would be better to insist on the ethical argument rather than the arguments of taste and tradition.

Unsurprisingly, consumers of foie gras downplay the ethical problem of force-feeding and the trade in foie gras, but they are nevertheless aware of the ethical problem. This result prompts us to focus on this ethical problem, in the hope that more and more consumers will abandon this morally uncomfortable product.

There are major gaps in information, both on the ban on force-feeding in Switzerland and on the fact that the magret comes from foie gras production. It seems necessary to focus information on younger people. This should be one of the main tasks of Stop Gavage Switzerland, which would certainly reduce the number of consumers.